What Happens When You Build a Racetrack in the Middle of a Neighborhood?

A Real-World Preview of What Walton County Can Expect from Emerald Coast Motor Club

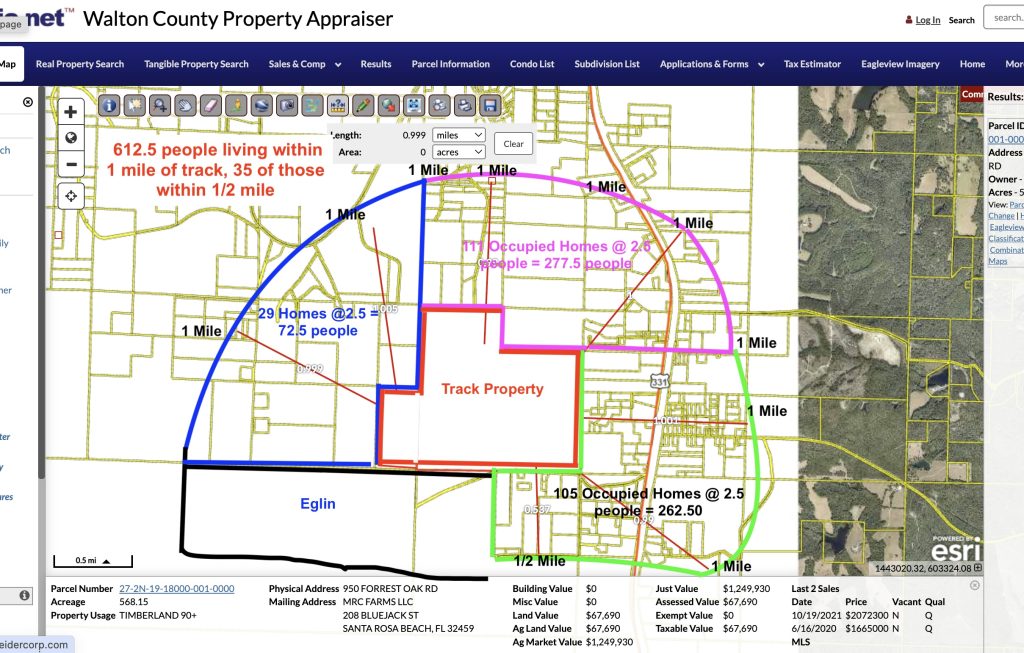

We don’t have to guess what will happen if the proposed Emerald Coast Motor Club (ECMC) is built among quiet rural neighborhoods in Walton County—where more than 600 residents live within one mile of the site.

We already have a real-world case study.

The Vancouver Island Motorsport Circuit (VIMC) in British Columbia, also designed by Tilke GmbH & Co. KG—the same firm selected for ECMC—shows exactly what happens when a private racetrack club is dropped into the middle of a residential area.

A Nearly Identical Setup — and a Predictable Outcome

VIMC was built in an amphitheater-like valley surrounded by the Sahtlam neighborhood, much like ECMC’s proposed site in Walton County. The surrounding geography naturally amplifies sound. From the day it opened, noise became the community’s number-one issue.

Neighbors who were promised quiet operations and limited use instead found themselves living with near-constant disruption. What was marketed as a “motorsports playground” quickly proved incompatible with residential life.

The same language—“exclusive, private, controlled”—is being used here in Walton County. But the Vancouver Island example proves that when you build a racetrack in the middle of a neighborhood, it’s not the members who live with the noise—it’s everyone else.

What Happened on Vancouver Island

Like the proposed Emerald Coast Motor Club, VIMC was marketed as an “exclusive motorsports country club.” It promised limited operating hours, quiet technology, and top-tier sound management. What residents in the Sahtlam and Cowichan Valley neighborhoods actually got was years of constant disruption.

Within weeks of opening in 2016, complaints began pouring in. The circuit sits in an amphitheater-like valley surrounded by homes and family farms, where the terrain naturally amplifies noise. Independent sound studies confirmed what neighbors already knew: the track’s acoustics carried far beyond its property line.

Residents said the sound wasn’t just loud—it was relentless, with engine testing, track days, and private events running far beyond what they were told to expect. The community organized, filed noise complaints, and pushed the Municipality of North Cowichan to review the track’s permit.

In 2018, when local officials denied a major expansion request, VIMC’s ownership group filed a $50 million (CAD) lawsuit against the municipality, claiming lost business opportunity. The case dragged on for years, draining public resources and creating deep division between residents, the local government, and the business community.

At one point, analysts warned that losing the case could force property taxes to rise by more than 130% to cover damages. Even after the lawsuit was settled and VIMC scaled back operations, noise complaints persisted.

Nearly a decade later, the Cowichan Valley community remains split over the project’s legacy. Property owners near the circuit continue to report reduced quality of life, and the local government has had to allocate ongoing resources to manage disputes related to sound and land use.

The key takeaway:

Even a well-engineered, internationally designed racetrack can’t overcome the wrong location. The terrain, the surrounding homes, and the community context matter—and when those are ignored, the cost is measured in lawsuits, legal fees, and neighborhood division.

Vancouver Island proved it. Now, Walton County is being asked to approve nearly the same model—by the same design firm, in a similar amphitheater-like setting, surrounded by hundreds of residents.

It’s not speculation. It’s a preview.

A Location That Makes No Economic Sense

Beyond quality-of-life concerns, the Emerald Coast Motor Club’s location doesn’t make sense economically.

Every other Tilke-affiliated motorsports club in Florida—The Concours Club (Miami), The Motor Enclave (Tampa), and P1 Motorsports (Port St. Lucie)—is positioned near major metro areas with deep concentrations of wealth, car culture, and easy access to international airports.

- Miami has more than 35,000 ultra-high-net-worth individuals (UHNW), one of the densest luxury markets in the U.S.

- Tampa Bay has roughly 9,000, supported by a strong corporate base and motorsports community.

- Palm Beach / Treasure Coast holds around 14,000, with a long-established luxury automotive culture.

- Walton County, by comparison, has a UHNW population representing well under 1% of those totals—and most of it is located in South Walton.

That imbalance matters. Racetrack country clubs depend on a narrow but extremely wealthy customer base—people willing to spend $100,000 or more per year on memberships, storage, and vehicle logistics. Walton County and the surrounding areas don’t have that demographic concentration, nor the airport access or infrastructure to draw it in.

Simply put:

- The wealth base exists but is too small and too far away,

- The local income base can’t sustain a luxury membership model, and

- The location is inconvenient for the clientele this kind of club targets.

Even the strongest business model can’t overcome those fundamentals.

A Clear Warning for Walton County

VIMC and ECMC share the same formula:

- Same design firm (Tilke GmbH & Co. KG)

- Same private “motorsports club” model

- Same amphitheater-like geography surrounded by family neighborhoods

We don’t have to imagine how this story ends.

If Walton County approves this project, it will be the only Tilke-designed club in the United States we could find built directly within a residential area—and the only one located far from a major metro area or easily accessible international airport.

That combination proved disastrous in Canada. There’s no reason to believe it will turn out differently here.

The Takeaway

Emerald Coast Motor Club isn’t just a bad fit for the neighborhood—it’s a bad business decision waiting to become the community’s problem.

Vancouver Island showed what happens when you ignore geography, population, and common sense.

We don’t have to guess what will happen here.

We already know.

This article represents community commentary and analysis regarding the proposed Emerald Coast Motor Club project in Walton County, Florida. It is based on publicly available data, comparable projects, and research into community and economic impacts. The intent is to inform and encourage public discussion about the suitability and long-term viability of this type of development.